Often when we talk about dietary evidence at archaeological sites in Alberta, we are referencing a multitude of game animals, such as bison, elk, moose, etc. What is often missing from these dialogues is the reliance First Nations had on native and traded plants. For the most part, organic material does not survive the test of time; this is especially the case in Alberta’s boreal regions where acidic soils rapidly decompose organics. However, missing data does not mean it was not there in the first place. A wide variety of plant species were utilized by Alberta’s First Nations for subsistence purposes. At archaeology sites, evidence of plant remains can be recovered from sediments, stone tools, and ceramics. Plant microfossil analysis is one method that can be used to identify what plants people were using in the past.

Plant microfossil analysis is the identification of microscopic phyotoliths, starch grains, and pollen. Phytoliths are silica structures on living plants that preserve when the soft tissue does not; starch grains are plant structures that store glucose; and pollen grains are the male microgametophytes of seed plants. These microfossils can sometimes be found on archaeological artifacts such as ceramics, mortars or pestles, and viewed under a microscope for plant identification.

In southern Alberta, and throughout the northern Plains, a cultural group known as the Avonlea Complex is present in the archaeological record from about 1350 to 1100 years ago. This group is mostly identified through their projectile point and pottery styles. Eight Avonlea sites are the subject of a master’s thesis that used plant microfossil analysis to find evidence of plant domesticates such as, maize, beans and squash, and native plants (Lints 2012). Although there are no Alberta sites represented in this study, the presence of domesticated plants in Avonlea contexts at sites in Saskatchewan, and one in Manitoba, supports the likelihood that these plant foods were widespread throughout the Avonlea Complex. The Gull Lake site is located 65 kilometers from the Alberta border and the Garratt site is located on the Moose Jaw River, on the south side of Moose Jaw city. These are just two examples of Avonlea sites with positive identification of maize and beans. In addition, a large number of wild plants (berries, roots, and tubers) including wild rice were identified by Lints (2012) at his eight study sites.

At an archaeological site on the west side of Calgary, residue recovered from grinding tools provided evidence of people processing native plants, including Saskatoon, chokecherry, native grasses, possibly prairie turnip and maize. The presence of maize at the site may indicate long distance Precontact trade networks (Zarillo and Koomyan 2006).

Another 176 archaeological sites across western and central Canada were looked at for evidence of plant use. Maize, beans and squash were sometimes found in combination, with higher amounts of wild rice in areas with fewer beans. The preference for wild rice in the southern boreal forest, as opposed to bean, could be a result of cultural and/or environmental factors, and squash was rare across the entire study. Most of the sites in this study dated to 2500 to 1000 years ago (Boyd et al. 2014).

Evidence of plant use by First Nations is also present in written accounts and observations. Some of the native plants that people used included strawberries, wild onions, tubers, roots, gooseberries, wild currants, saskatoons, chokecherries, buffaloberry, raspberry, bearberry and roots such as wild carrot and wintergreen. First Nations in the Cypress Hills of southeastern Alberta used a wide variety of native plants (Bonnichsen and Baldwin 1978).

Clearly, plants, both domesticated and native, were used to supplement the diet of First Nations. Often, this is overlooked in the archaeological record, with less focus on habitation sites, and more on large-scale bison kill-sites. A lack of visible organic evidence also has a large role to play in this misconception. The use of plant microfossil analysis at archaeological sites in Alberta can contribute a great deal to our understanding of early First Nations plant use.

Written by: Alex Burchill, Archaeological Survey

References

Bonnichsen, R. and Baldwin J. Stuart, 1978. Cypress Hills Ethnohistory and Ecology. Occasional Paper No. 10. Archaeological Survey of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Boyd, M., Lints, A. Surette, C. and Hamilton, S., 2014. Wild Rice (Zizania spp.), the Three Sisters, and the Woodland Tradition in Western and Central Canada. In Maria E. Raviele and William A. Lovis eds. Reassessing the Timing, Rate, and Adoption Trajectories of Domesticate Use in the Midwest and Great Lakes. Special Paper No. 8, Midwest Archaeological Conference, Inc.

Burchill, A., 2014. Plant Microfossil Analysis of Middle Woodland Food Residues, Northern Minnesota. MA Thesis, Lakehead University, Department of Anthropology.

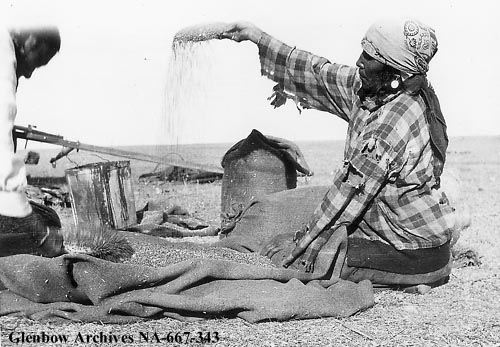

Glenbow Library and Archives’ website/Image #NA-667-343 (ww2.glenbow.org)

Lints, A., 2010. Evidence of Domesticates From Early Ceramics of the Northern Plains: An Analysis of Avonlea Cultural Materials (AD 300-1000). MA Thesis, Lakehead University, Department of Anthropology.

Zarrillo, S. and Kooyman B., 2006. Evidence of Berry and Maize Processing on the Canadian Plains form Starch Grain Analysis. American Antiquity 71(3), 473-499.

One thought on “Early Plant Use in Alberta”